For those wishing to return to contact sports, exertional testing is a requirement to ensure a full metabolic recovery has occurred beyond symptom absence, and there are no lingering concussion implications that could be worsened though contact. A concussive injury causes metabolic disturbances to the brain that can be restored with rest, manual therapy  and rehabilitative homework. Over this period, patients will experience a reduction in symptoms at rest and during progressive physical and mental activities.

and rehabilitative homework. Over this period, patients will experience a reduction in symptoms at rest and during progressive physical and mental activities.

The exertion test itself will consist of a series of mental and physical tasks done in combination to evaluate for symptom re-creation. Cognitive evaluation will be tested before and after the exertion to compare results for abnormalities. As with other stages of return to play, clients should be monitored for any of the 22 symptoms of concussion to appear over a 24 hours time period.

What is the rationale for exertional testing?

Relying of symptoms (of the lack thereof) to make return-to-play decisions puts concussion care practitioners in an extremely difficult position. Symptoms do not reflect true recovery of the brain after a concussion, especially symptoms reported while at rest. In fact, in a recent study, 25% of participants still had ongoing impairment (as seen on neurocognitive testing), despite being cleared using SCAT5 and physical evaluation at rest.

If the brain is still in recovery, it is vulnerable to secondary impacts. As small as bump may be, concussion symptoms may feel as if they have returned, especially if a full recovery has not occurred in the first place. If allowed time to heal, research has suggested that a full metabolic recovery should have little to no additive or cumulative effects of a second concussion. (1,2)

While a patient may feel as though they have fully recovered, there may be small cognitive, visual or vestibular abnormalities not sensed with everyday challenges. Studies have shown that doing neurocognitive testing after high cognitive and physical exertion will show 28% more sensitivity to impairment then doing the tests after resting. (3,4)

Who is a candidate for the test?

Exertional testing may be done after a client has reached stage 5 (non-contact practice) of their graduated return-to-play process. Clients are expected to be able to handle:

- Environmental stress (weather demands, sun, noise)

- External cues of performance (carry out demands of the coach and teammates)

- Reaction time (hands, feet, visual, orientation)

- Built up cardio intensity/endurance

What to expect for the test?

- Blood pressure/heart rate check

- Symptom assessment

- Cognitive assessment

- Cardiovascular test

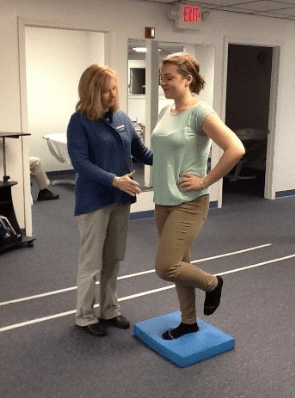

- Physical/mental testing

- Re-testing

How to Pass the Exertion Test

In order to pass the exertion test and receive return-to-contact clearance, clients must demonstrate the following:

- Must remain symptom free throughout the entire duration of the testing.

- Must complete the tests with high intensity, good form and mental competence.

- All post-testing physical and cognitive measures match or improve beyond their pre-testing values or pre-season baseline test values (if available).

- Must remain symptom free after the test for 24 hours.

How are the results interpreted?

Objective testing values such as visual processing speed, reaction time, and cognitive abilities are measured for direct comparison before and after the evaluation. The numbers before and after the test should be relatively the same: In healthy individuals, scores tend to improve over time due to a learning effect. However those with a lingering concussion will demonstrate scores worse than pre-test and/or baseline values. If a patient demonstrates a worsening in performance, then they are considered not ready for contact activities. These patients will be given more rehabilitative drills and time to achieve a full metabolic recovery before re-exertion testing.

Author: Alee Skoblenick, Athletic Therapist – Collegiate Sports Medicine (Red Deer Main)

References

- Vagnozzi R, Tavazzi B, Signoretti S, Amorini AM, Belli A, Cimatti M, et al. Tempral Window of metabolic brain vulnerability to concussions. Neurosurgery. 2007; 61(2):379-89

- Vagnozzi R, Signoretti S, Tavazzi B, Cimatti M, Amoribi AM, Donzelli S, et al. Hypothesis of the post-concussion vulnerable brain: Experimental evidence of brain injury: a multicentre, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic study in concussed patients. Brain. 2010; 133(11)3232-42.

- Whyte EF, Gibbons N, Kerr S, Moran KA. The effect of a high intensity, intermittent exercise protocol on neurocognitive function in healthy adults: Implications for return to play management following sports related concussion J Sport Rehabil. 2015; 24(4)

- McGrath N, Dinn WM, Collins MW, Lovell MR, Elbin RJ, Kontos AP Post exertion neurocognitive test failure among student athletes following concussion. Brain Inj. 2013;27(1):103-13